The Night of the Long Knives saw gang rivalries played out in public, while authorities, witnesses looked the other way.

As a writer setting my crime novels in the Townships of the 1970’s, I’ve had no shortage of background material to sift through. It was an incredibly rough era for so many reasons, a time when a lot of folks lived life close to the bone. Playing a prominent role were the outlaw bikers, shooting up the streets of Sherbrooke and bringing the city firmly into the fold of organized crime. And the local memory of those times, including an all-out bloody turf war, has been overshadowed by the violence that came later.

In the 1950’s and 60’s lots of folks embraced the post war prosperity and got motorcycles. Little clubs started to pop up, groups of like-minded folks who enjoyed a beverage or two and a ride in the country on the weekend. These were the 99%, the law-abiding bikers who often get overlooked.

Then there was the other 1%. In Sherbrooke in the 1960’s there was a gang known as The Dirty Reich, a group of bad boys who saw the potential in organized crime, with revenue streams from things like drugs, prostitution, and human trafficking. They also did a lot of other violent, cruel, and nasty things, seemingly just to be assholes. If you were “visibly” gay, or not white, or different in any way they might pull over and give you a beating. Despite this, the Dirty Reich even had its own Catholic priest, Father Jean Salvail.

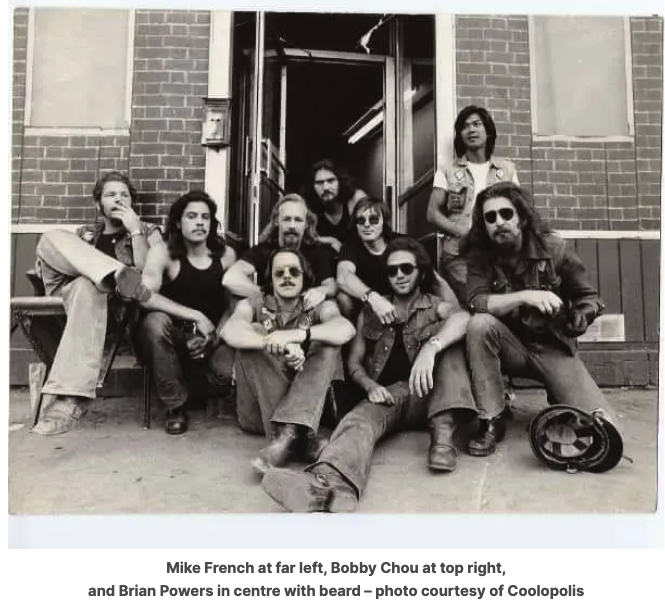

By the early 1970’s the priest had left the scene, and The Dirty Reich had become the Gitans (Gypsies), now locked in an uneasy coexistence with the Atomes (Atoms) for control of Sherbrooke’s illicit trades. In an era where the murder rate in Montreal was roughly three times what it is now, and in which that city was hailed as the bank robbery capital of North America, the Gitans and Atoms were getting rich by filling the void of vice in the Sherbrooke cityscape.

Why were things so rough in the 1970’s? There was a lot of political unrest, from the Front de Liberation du Quebec bombings to the rise of separatism. The economy was slowing, and Sherbrooke was in the midst of transforming from a predominantly English-speaking factory town to predominantly French-speaking one. Sherbrooke was rough, and life less easy than it had been. There’s even an unproven theory that the lead in gasoline car exhausts of the time made folks more aggressive.

The Townships countryside wasn’t immune to the uptick in violence. Members of both gangs would tour about on their motorcycles, striking fear into the locals and bringing the hard drug trade to the smaller towns. On top of their Montreal Street headquarters in Sherbrooke, the Gitans even had clubhouses in Cowansville and Frelighsburg.

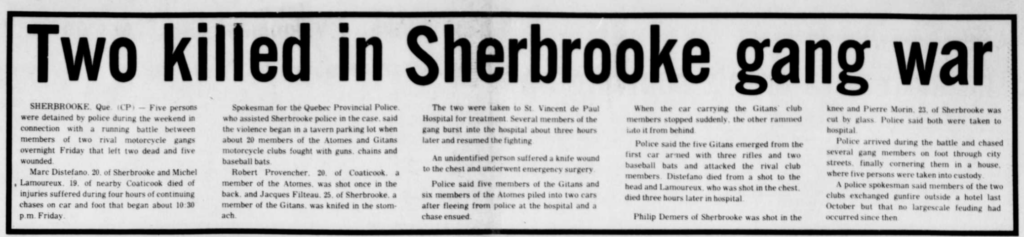

For the Gitans and the Atomes things came to a head on the night of March 15, 1974. Three Gitans were having a few beers at the Brasserie La Boustifaille on King East when a half-dozen Atomes showed up. The trash talk began, and before long they collectively decided to take things outside. Next thing you know there are about 20 bikers from the two clubs, armed with firearms, knives, chains, and baseball bats, beating on each other in the parking lot.

In the ensuing rumble, Atome Robert Provencher was shot in the back and fled the scene on foot, while Gitan Jacques Filteau was knifed in the guts. His buddies rushed him to the nearby St. Vincent de Paul hospital emergency room. Provencher staggered as far as Cartier Street before collapsing outside an apartment, begging for an ambulance. The ambulance came and brought him… to the same hospital where Filteau was being treated.

Of course, fellow Gitans came to see Filteau, while Atome members came to see Provencher. Hostilities broke out in the emergency room, and the lone security guard was easily overwhelmed. In the midst of the melee the Sherbrooke Police were called in. They had no sooner restored order than word came that more bikers were on their way, and efforts refocused on keeping them out of the various hospital entrances. They called in the Sûreté du Québec to lend a hand.

Somewhere in all this five Gitans got into a car and left, pursued by six Atomes in another car. At the corner of 12th Avenue and King East the Gitans slammed on the brakes, and the two cars collided. The Gitans got out, surrounded the Atomes car and opened fire. Marc Distefano, 23, was shot in the head and killed. Michel Lamoreux, 19, was hit in the chest and killed, having been inducted into the gang six hours earlier.

Here comes what is perhaps the strangest twist in the entire affair: That summer, after months of seeming police inaction, four people were arrested for the murders of Distefano and Lamoreux. By that fall, all were acquitted. For all the violence in what became known locally as The Night of the Long Knives, not a single person was convicted of a crime. “Les Gitans “blancs comme neige,” declared the headline in La Tribune.

Indeed, despite continued outbreaks of sporadic violence and even a provincial police commission to study the province’s biker gangs, little was done. By 1979, Sherbrooke Record Editor James Duff declared “… we think the age of the gangs has passed.” Meanwhile the Gitans slowly picked off or patched over members of the Atomes, and by 1984 the Gitans themselves were patched over, founding the Sherbrooke chapter of the Hell’s Angels.

Apparently on this prediction, Jim Duff misread his tea leaves. Just over 11 years later, the Sherbrooke chapter of the Hell’s Angels invited in five members of the North Chapter to their Lennoxville clubhouse, and shot them. Setting the early stage for the province-wide biker war of the 1990’s.