Month: April 2024

The Georgeville plane crash that left observers scratching their heads.

Why would Satan’s Choice be involved the marine salvage business?

Ed note: This originally appeared earlier this year in The Record’s Townships Weekend section

By Maurice Crossfield

Every now and then you come across an oddball story, one that doesn’t make sense and raises more questions than it answers. Like why, when a Royal Canadian Air Force transport plane crashed on Lake Memphremagog in 1968, did it end up being salvaged by a group of outlaw bikers a decade later?

On January 7, 1968 (I wasn’t even a month old yet), Flight Lieutenant J. D. Evans and navigator Flight Lieutenant J. F. Morrow of 401 Auxiliary Squadron, based out of St. Hubert, were practicing landings on Lake Memphremagog near Georgeville with a De Havilland Otter. The single engine Otter was used in the RCAF for light transport and search and rescue operations until 1980, and many of them are still in service today, primarily as bush planes serving remote communities. They can be kitted out with conventional landing gear, floats for open water landings, or skis for winter touchdowns.

On one of the practice landings the ill-fated aircraft broke through the ice. Then the fuselage sank into the water. The two men managed to scramble out of the downed aircraft, giving their wedding tackle a good chilly soaking in the process.

Fortunately, the crash had a witness in the form of 18-year-old Réal Bernais, who had been hanging out on the Georgeville wharf. He was probably watching the plane. Bernais jumped on his snowmobile and raced out to get the two men, bringing them back to Henry McGowan’s boarding house to warm up and dry out. As they sipped hot coffee, they heard an explosion as the airplane caught fire. Within minutes the fire was out, the plane having sunk into 280 feet of water.

Over the next decade the wreckage of the ill-fated Otter was the subject of several salvage attempts. Marine Industries of Montreal apparently spent $30,000 to locate and raise the aircraft, but with no success.

Then in 1976 Montreal-based Lafitte Salvage purchased the salvage rights for $1,000. Using cutting edge technology such as closed-circuit cameras, they located the plane and managed to haul the tail and fuselage back to the surface, taking the wreckage to dry land in Georgeville, and later Magog. The salvagers refused to comment on rumours that a safe was found on the plane.

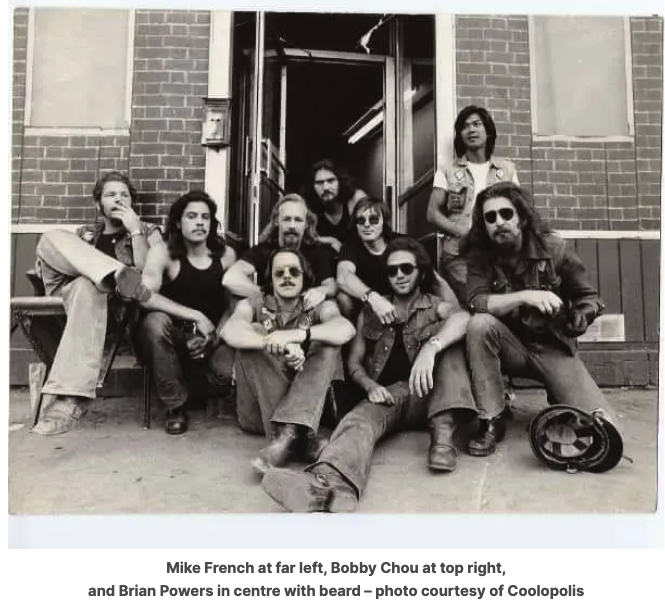

Here’s where things start to get interesting: It turns out that Lafitte Salvage was never a registered company. But the names of the five-man crew were known to the authorities: Brian Powers, Robert Chou, Michael French, Michel Veillette and Jean-Paul St. Michel. All members of the Satan’s Choice Motorcycle Club. If you start digging around in old newspapers looking for organized crime in the 1970’s, these names come up over and over. There was a gang war that saw Satan’s Choice and the Outlaws shooting it out with the Popeyes and Hell’s Angels. It was a bloody conflict in a particularly bloody era of Quebec history.

Powers ended up shot at his home in Montreal’s West Island in 1979. French was gunned down by West End Gang enforcer and hitman Jackie McLaughlin in 1982, his body found near Kahnawake. Chou died in 2018 of liver failure. I’m not sure what became of the others, but as you can see, these weren’t classically trained salvage experts living good, clean lives.

There are quite a few aspects of this that don’t add up: Firstly, why did Evans and Morrow try to land on Lake Memphremagog when the ice wasn’t thick enough to support an aircraft of that size? What caused a downed, nearly drowned airplane to explode well after the men were rescued? And then, why was security around the crash site so lax? If a military aircraft goes down, wouldn’t the RCAF have sent its own people to secure the site, and maybe send military divers in to examine the wreckage? I am unsure of the rules back then, but these days there would have been a full Canada Transportation Safety Board or a military investigation, with experts going over every inch of the plane and reporting on their findings. Instead, the armed forces sold off the salvage rights to whoever, with no regard for things like security, crash causes, or who they were giving military property to.

And why were a bunch of outlaw bikers doing underwater salvage work? News reports from the time said the skis from the plane were worth a few thousand dollars. The engine still turned freely and the three-bladed propellor was intact. But these guys were more accustomed to making bigger money in other domains, like dealing drugs and pimping out strippers and prostitutes. Stripping crashed planes for parts seems like more actual work than they were used to. How come they managed to raise the plane when the experts at Marine Industries failed?

Add to that the rumors of a safe on board. Was there something valuable on the Otter? I doubt it. The 401 Squadron was air reserve. These were part time guys, weekend warriors, who seem to have been practicing landings. Why would they have been carrying anything of value?

These are all questions that will remain unanswered. In fact, this story would likely have been forgotten by all but a few people if the late John Allore hadn’t come across it. While John Allore died in an accident nearly a year ago, his website https://theresaallore.com/ lives on. It’s a fascinating archive of true crime in the Eastern Townships and beyond, dedicated to finding who murdered his sister Theresa, when she was a student at Champlain College in November 1978.

Hopefully that’s a story we can still find answers to.

The Future, by Catherine Leroux, translated by Susan Ouriou

On a rainy and snowy March night I took part in CBC Reads, And So Does Lennoxville, a fundraiser for that town’s library. While my arguments in defence of this fine novel didn’t carry the night, The Future did go on to win the CBC’s top prize. Here’s why:

The Future is Catherine Leroux’s alternate history of Detroit, in which the city was never surrendered to the Americans, and my choice for the Canada Reads theme of the one novel that carries us forward.

I have to say right away that The Future is a beautiful, poetic translation. As both a writer and a translator, I am impressed by both Leroux’s skill at creating a dystopian future, and the deft hand of translator Susan Ouriou. Translation has its own particular challenges at the best of times, but Ouriou handles her task with grace.

In The Future, Fort Détroit is a French-speaking Canadian city, but still has many of the problems that we have seen plague real-life Detroit recent years: Pollution, poverty, the legacies of racism and colonialism. However, in this alternate future, Fort Detroit society has broken down even further: There’s little to be had in terms of police or fire protection, and city services like water and sewage regularly break down. People must rely on themselves and those close to them.

Yet destroyed buildings, such as the city’s leaning Tour de Lys, or even neighbourhood houses, slowly, mysteriously, regenerate themselves. There are magical elements, never clearly explained, that tap into the reader’s imagination. To me this is where the most profound aspects of storytelling take place, in a sense prying our minds open to the possibilities of the universe.

Gloria comes to Fort Detroit following the murder of her estranged daughter Judith, and the disappearance of her granddaughters. She wants to find her grandchildren, and the truth of what happened to her daughter. Nearly destroyed by grief, she slowly builds bonds with neighbours, and begins to learn of the resilience that keeps them going, despite the harsh realities of their existence. They grow food in abandoned lots, gather necessities from the devastated environment around them. Comfort each other in times of loss.

Gloria also discovers a group of the city’s children who live in the nearby Parc Rouge ravine. Runaways, or perhaps abandoned or orphaned by their parents, these kids have established their own society, complete with its own rules and hierarchies, all based on the greater common good. In short when these children are abandoned by society, they create a society of their own. Kind of like Lord of the Flies, but far more humane, compassionate. They may grumble about their leaders, but when push comes to shove, the common good wins out.

And this to me is what makes The Future such a compelling book to move us forward. At its core it is a book about community. Society may have collapsed, but community endures. Community can mean many things, from neighbours helping neighbours to children supporting each other when adults can’t, or won’t. Much like the buildings regenerating themselves, if a community breaks down, another form of bonding between people moves in to take its place. And in these varied forms of community, we see reflections of ourselves.

In this age of anxiety and insecurity, The Future is a reminder than in grim times we don’t have to go it alone. Indeed, those darkest of times are when we need to reach out. To build bonds, to serve others, and to receive support in return. Plain and simple, we are social creatures.

We don’t control much in this life. The one thing we all have a measure of control over is HOPE. Hope for a kinder future in which people help each other, despite the challenges. Hope for better times, even when the world around us seems hopeless. Indeed, the absence of hope, like the absence of community, invariably leads to the end of humanity.

Despite its dystopian backdrop, The Future is ultimately a hopeful work, providing readers with plenty to think about, and a vision for a way forward. It may seem like the end of society, but in that ending are numerous small beginnings. We are all more resilient than we can imagine and more resilient collectively than alone. The Future is a reminder of those simple facts.

Seneca Paige: Justice of the Peace, MLA, counterfeiting king

Dunham’s first cottage industry was a real money maker

People often speak dismissively of our history, no doubt fuelled by that teacher who recited names and dates, making sure to never stray too far from the established curriculum. History is something that happened elsewhere, written by and for kings, leaders and generals who dictated the terms of victory, or rarely, accepted defeat.

But history is so much more than that. It is the lived experiences of people just like you and me, who worked hard, often died young and struggled, not merely to be successful, but just to survive. While I love history, I hold no illusions about “the good old days.” Like many of you, I’m alive because of medical science and modern prosperity. I’ve never had scurvy, tuberculosis, or faced the threat of starvation. It might not seem like it, but we live in the best time to be alive.

As a storyteller though, I love history. I love imagining myself not in the shoes of Napoleon or Churchill, but in the well-worn leather boots of more regular folks. And if there’s one man I’d love to do an interview with, and who refutes the Townships myth of “nothing interesting ever happened here,” it would be Dunham’s counterfeiting king, Seneca Paige.

Before we dive into Paige’s life, a quick bit of background: In the early days of the United States there wasn’t a single US currency. Instead, banks issued notes that served as legal tender. These notes varied greatly in style and substance, and early settlers with an artistic flair often set out to recreate them, trading them for legitimate cash, gold, or using them to buy supplies. Counterfeiting was illegal in the US, but north of the border, making fake US bank notes wasn’t against the law. Having come from the States, some of the new settlers seized upon an opportunity, and a border that was, for the most part, still an imaginary construct.

Born in Hardwick, Massachusetts in 1788, Paige was a slippery critter from the get-go. He got busted in Jersey City in 1809 for passing a fake dollar bank note, but got out of that one. Then after being arrested for counterfeiting in Baltimore in 1812 he escaped custody. He got caught again in 1816 and managed an escape yet again. That’s when he moved to Cogniac Street in Dunham.

Not much of a street, barely even a road, stretching from near Selby Lake to North Sutton, Cogniac Street, now known as Hudon Road, became the counterfeiting capital of North America in the early 1800’s. And it’s here that our intrepid Mr. Paige really came into his own.

Paige built up a counterfeiting network of printers, engravers, couriers, and various folks all looking to cash in on counterfeit craze. Known officially as a wood merchant and building contractor, his main focus was making money. Lots of money.

The counterfeiter’s tool kit.

But there were others on Cogniac Street that he had to deal with. Ebenezer Gleason was an illiterate but clever man with a gang of funny money makers of his own. In a region and time where survival was a daily concern for most, Gleason prospered. Seemingly he saw the benefit of working for Paige and his people, contenting himself to playing second fiddle.

Not so for Turner Wing and his gang. In 1824 Wing led his gang of thugs, armed with pistols and swords, down the road to Paige’s lair. They hauled away about $4 000 in bank notes, copper plates, printing equipment and even a few of Paige’s crew, including his dear old dad, who ran the presses. Nobody messes with dad and gets away with it, so Paige and Gleason locked and loaded and paid the Wing crew a visit. By the time the dust settled all was returned, including dad, and Wing was allowed to continue his business, on a reduced scale.

Where were the cops, you might ask. This being early days, there wasn’t much for law enforcement. There was pretty much just Ephraim Knight, Bailiff for the District of Bedford. Knight tried his best, getting little more than the occasional beating and regular torment from the counterfeiters, known far and wide by now as Cogniackers.

By 1833 however, the tide began to turn, and the laws began to catch up. That summer an assortment of law enforcement types from both sides of the border surrounded and raided the Wing and Gleason compounds, hauling away large sums of legal and illegal tender, printing equipment and chemicals, and arresting thirteen people, including Ebenezer Gleason and four of his sons. Hauled to Montreal, they were all convicted, but only spent two years behind bars.

Walking between the raindrops once again was Paige, who was never convicted of a crime north of the border. But what does a criminal do when the counterfeiting business goes into decline? For Seneca Paige, politics, of course. He was given a large tract of land by the Crown, served a stint as a Justice of the Peace, and then in 1851 he became the Member of the Legislative Assembly for Missisquoi in the Province of Canada. He even has his own National Assembly web page, which makes no mention of his checkered past.

Today the Cogniac Street counterfeiters are all buried in one of the several cemeteries along Hudon Road. Ebenezer Gleason is in the Harvey Cemetery, Turner Wing in the tiny cemetery that bears the family name. Various others, little known or entirely forgotten, sprinkled amongst the more faithful in the Dunham East or Farnam’s Corner cemeteries.

But not Seneca Paige. He died in 1856 at the age of 68. Finally safe to return to the US, he was buried in Bakersfield, in Franklin County, Vermont. His tombstone states: “His Loss will be felt by many; particularly by the poor. He was truly the poor man’s friend.”