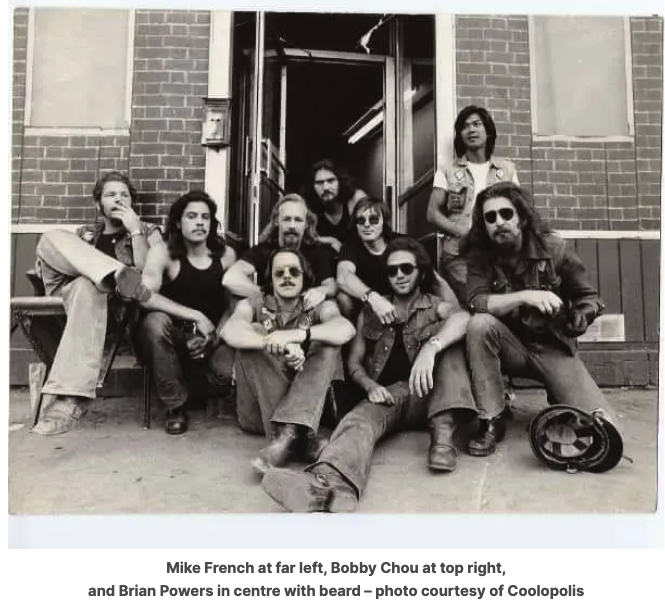

Raised on Montreal’s mean streets, he was a real life action hero.

If I ever decide to write a novel about a tough-as-nails cop who didn’t mind breaking a few rules to bring the bad guys to justice, I think I’d have to base him on the Sûreté du Québec’s own Albert Lisacek.

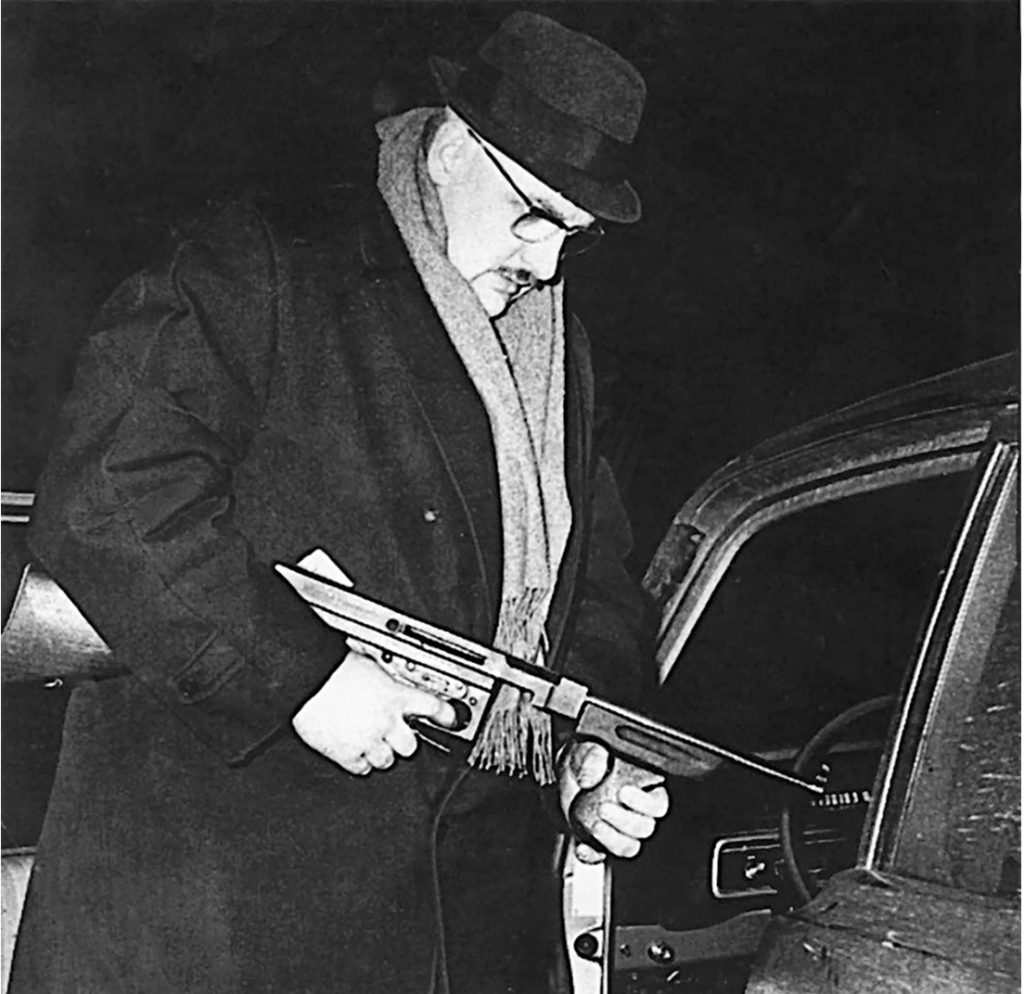

Albert Lisacek, seen here with his beloved Chicago Typewriter.

This guy had all the qualities you’d look for in a hard boiled, film noir cop. Born in 1933 in Montreal’s Mile End to Czechoslovak immigrant parents, Albert came by his physical attributes honestly. His mom, who was five-foot-eleven, gave birth to her three children at home, no doctor required. And dad was a former strong man in a Slovenian circus, who worked in shipyards and as a night watchman when he came to Canada.

Life in Montreal was rough in those early years, and Albert was often hounded by the neighbourhood bullies. One day, while being chased, 15-year-old Albert hid out in an old lady’s apartment until they went away. That was the moment he decided he wanted to become a police officer.

Fast forward five years and our young hero has been working out, tipping the scales at 250 pounds and standing at a respectable six foot-two. This made him ideal for his job as a bouncer at a St. Catherine St. night club. After some time working as a private detective, Lisacek joined the SQ at the tender age of 23.

His first job was guarding the jail cells at police headquarters. When one inmate in a group of eight got a little too mouthy, Lisacek went into the cell, locking the door behind him. He then proceeded to slap around inmates with his giant hands until the culprit was given up by the others.

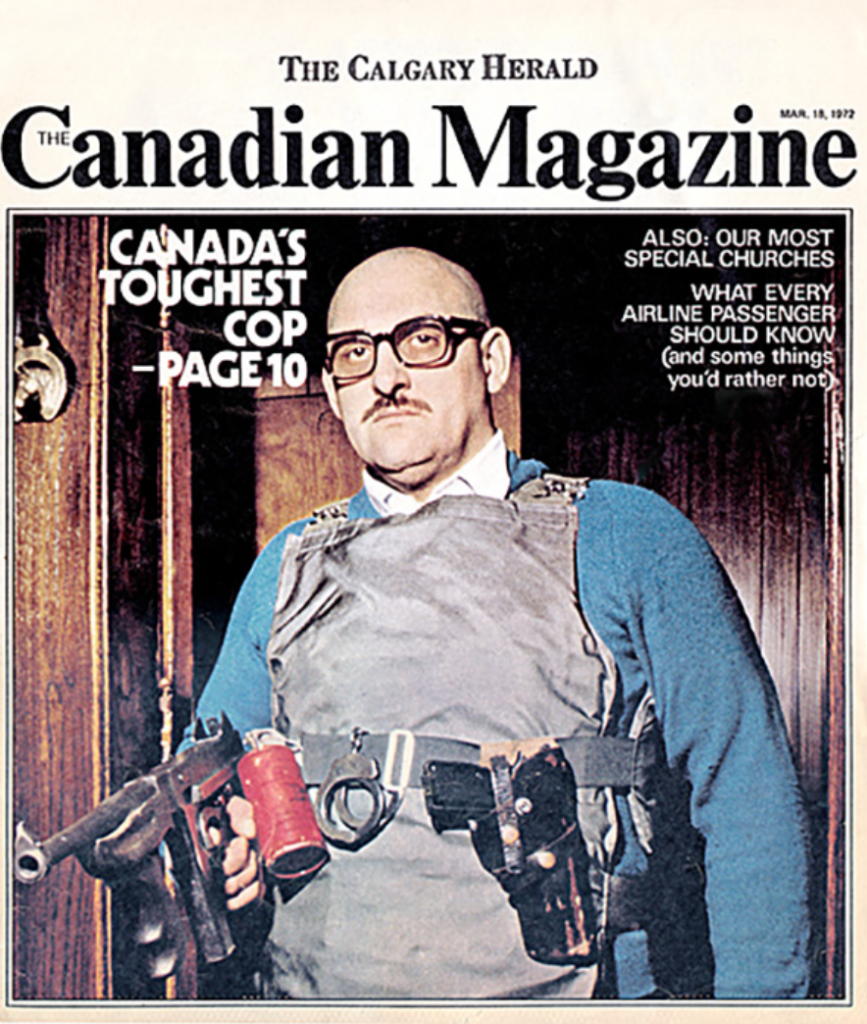

Before long Montreal’s criminals were calling him “Dirty Albert.” This, more than 20 years before Clint Eastwood made Dirty Harry a household name. His colleagues called him “Little Albert,” and later “Kojak” when he shaved his head.

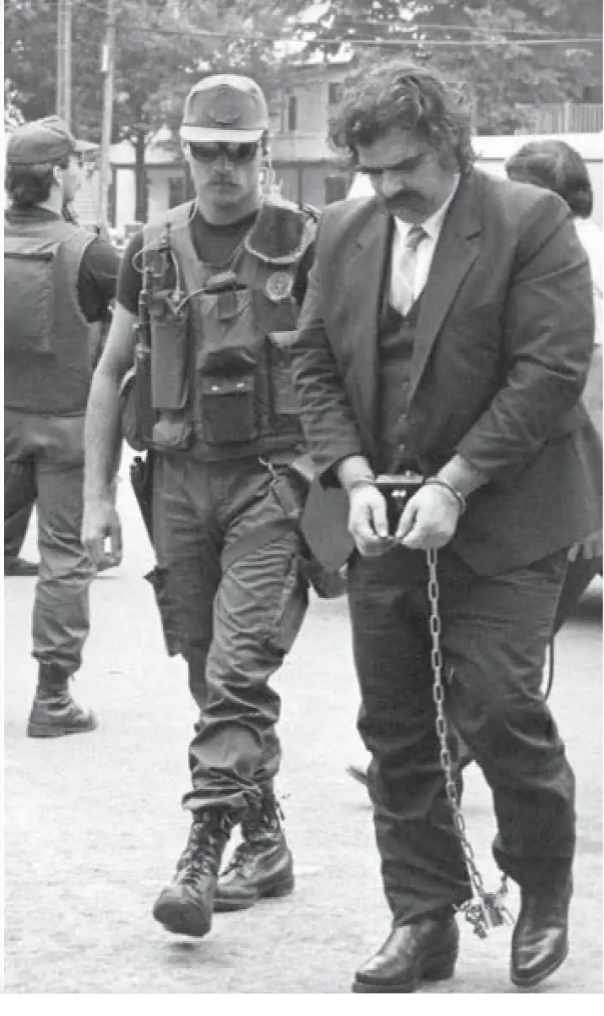

By 1961 Lisacek was promoted to detective. “I was good at getting rid of the bad people,” he told a reporter years later. Two years later he was a member of the SQ’s hold-up squad, where he became known for bringing his own Thompson submachine gun on raids. If you’ve ever seen a gangster movie set in the Prohibition era, you’ve seen a Tommy gun. Also known affectionately as a Chicago Typewriter. It spat out large, heavy .45 calibre slugs that could really make a mess. I really don’t think cops could get away with that sort of thing today.

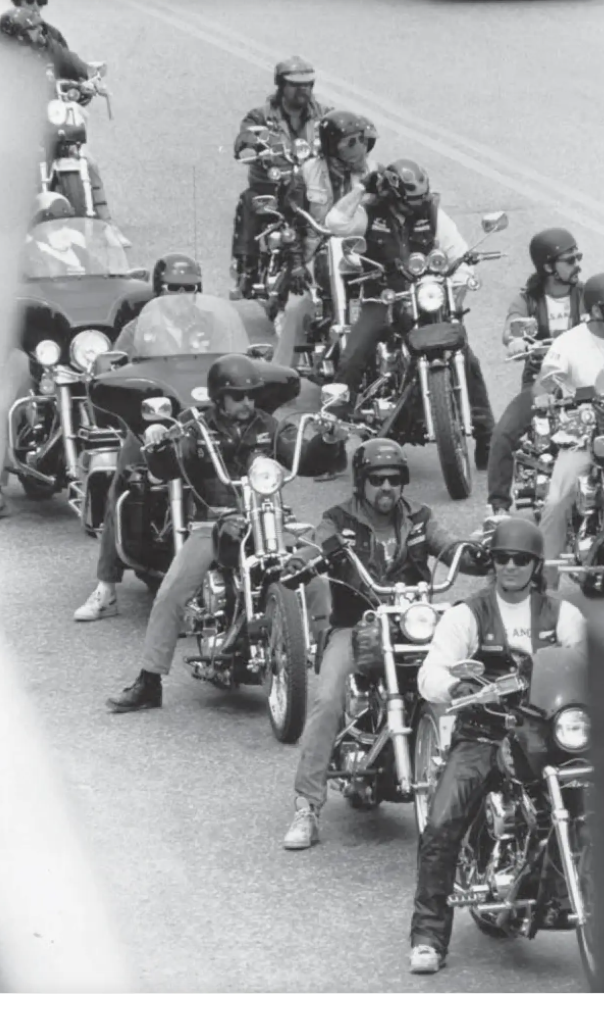

So Lisacek is on the holdup squad just as bank robberies are on the rise. Before long Montreal will be given the dubious title of North America’s bank robbery capital. And by the mid 1970’s the city’s murder rate is three times what it is today. There’s a lot going on, and Lisacek is in the midst of it all.

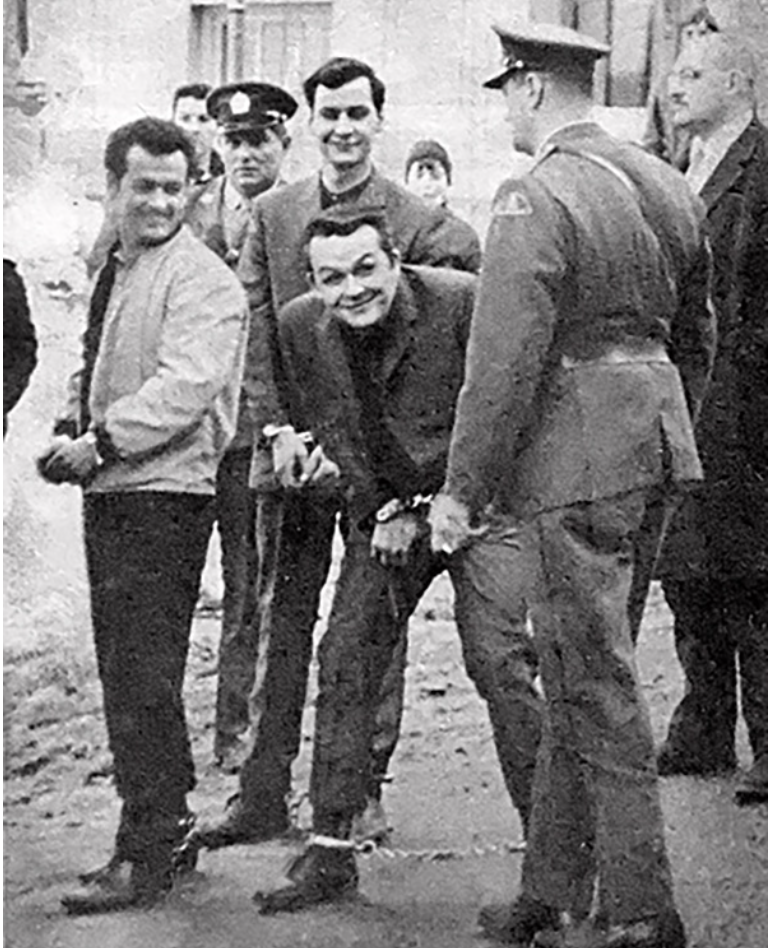

In 1969 Lisacek arrested Richard “The Cat” Blass for a bank robbery in Sherbrooke. Blass was a very, very bad man who had survived four assassination attempts and escaped from prison three times. At one point during the trial Lisacek saw a man from the audience lean forward, seemingly to give Blass something. Lisacek grabbed the man, dragged him out of the courtroom and smashed his face into the elevator door.

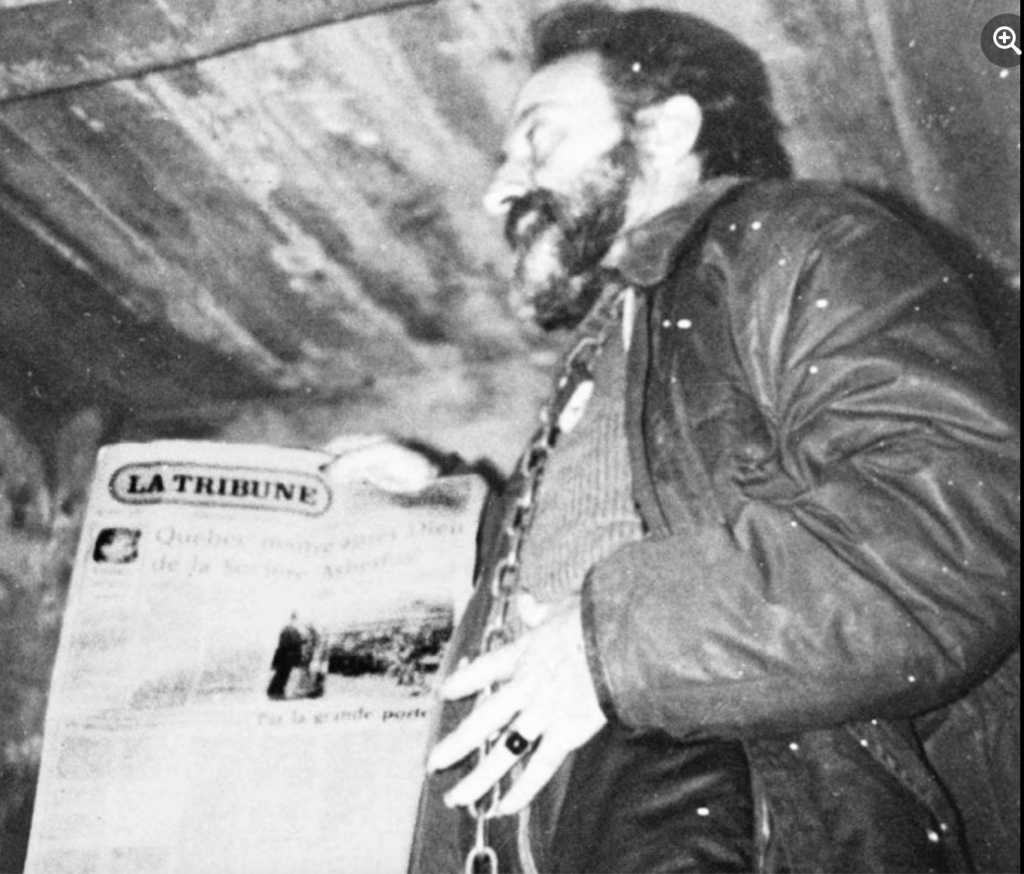

Richard “The Cat” Blass, seen here smiling for the cameras, was about as bad as it gets. Lisacek can be seen at the far right.

Man on the scene

Lisacek became Quebec’s most notorious cop, often at the centre of the latest news on Quebec’s crime scene. He was there in October 1970 when the body of Pierre Laporte, Quebec’s deputy premier, was found, murdered by the Front de libération du Québec. Two years later, while intervening in a robbery, the big man gave chase to three suspects. One of them ended up with, uh, his testicles shot off. In another case, a robber was running so hard to get away from the big man that he lost his shoes.

In 1975 Lisacek was on the trail of Blass once again. Blass had escaped custody, and while on the lam he locked 13 people in the beer storage room at the Gargantua Bar in Montreal, and then set the building on fire. All 13 died in the blaze.

The pursuit led Lisacek and his colleagues to a chalet in the Laurentian town of Val David. With Blass cornered in a bedroom, Lisacek agreed to let Blass put his pants on before coming out. When Blass stepped out of the room, the police opened fire. Blass was shot 27 times.

Lisacek, who would later state that what appeared to be a weapon in Blass’s hand was nothing more than a sock, never fired a shot.

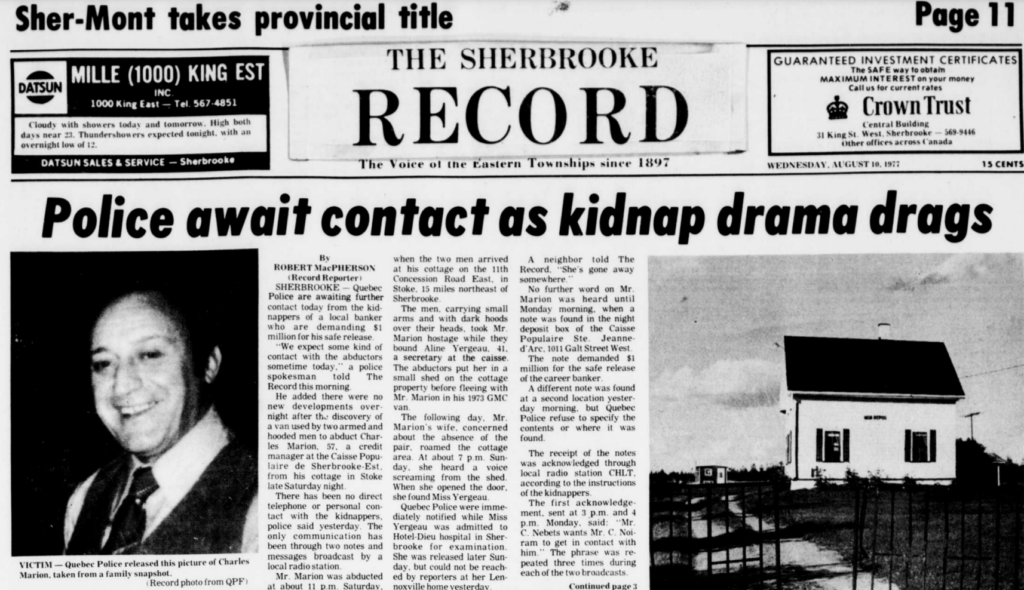

A study in contrasts: Note the other headlines.

Being at the heart of so much bloodshed caused Lisacek no shortage of grief at the hands of his SQ superiors. He was eventually moved to a desk job, his Chicago Typewriter retired. In 1981, at the age of 48 and with knee problems that made it hard to get around, Lisacek took early retirement.

His home life proved to be much quieter than working the mean streets. Devoted to his wife and dogs, he passed his days watching action movies and collecting John Wayne memorabilia. His beloved Claudia died in 1999, and he later remarried a cousin by marriage, Jacqueline Richer, who he doted on.

“He had a very tender heart,” said Richer. “When he saw there was no justice, he wanted to make justice.”

In 2012 Albert Lisacek, once the toughest cop in Canada, died of colon cancer. He was 79.

Quebec hasn’t had many homegrown action heroes on the silver screen. But they did have one in real life.