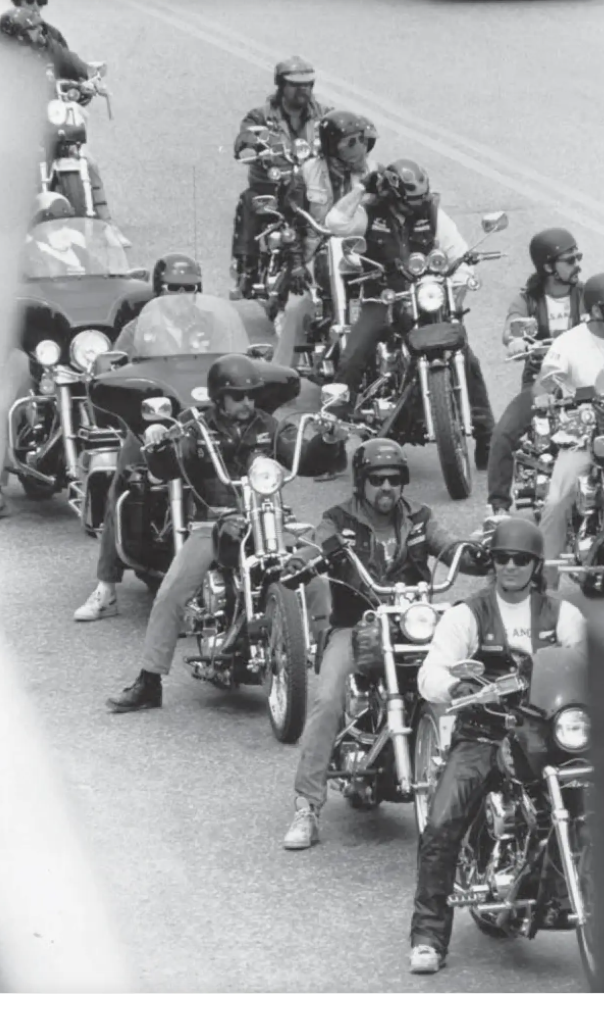

It was the party that laid the groundwork for a gang war that would shake Quebec for more than 15 years

By Maurice Crossfield

I missed an anniversary earlier this year. No, it’s not really one that should be celebrated. March 2025 marked the 40th anniversary of the Lennoxville Purge, in which five Hells Angels were gunned down at a party at the gang’s clubhouse and ultimately set the stage for the second Quebec Biker War.

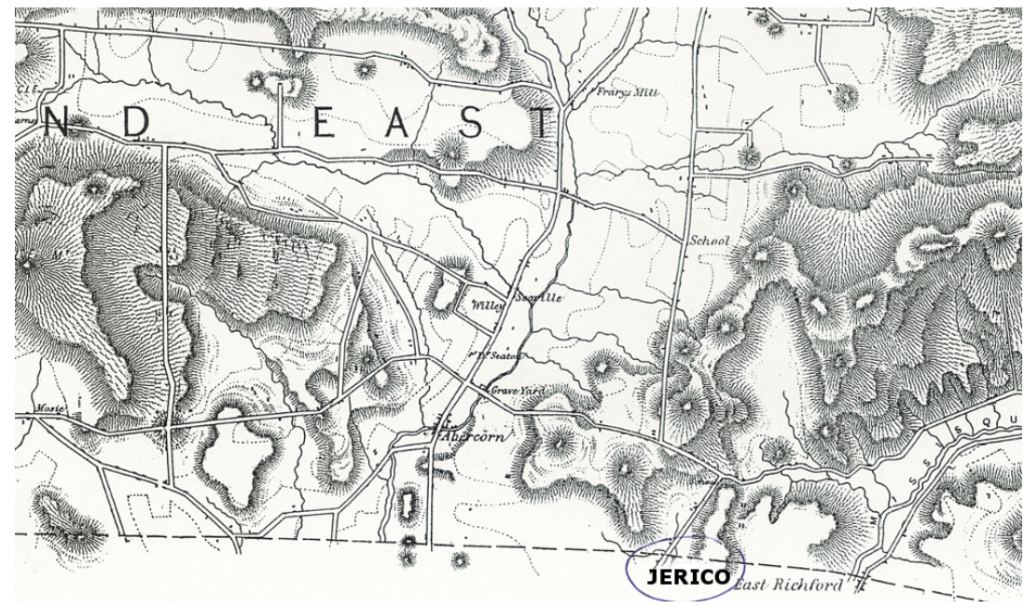

A little background first: Back in the 1970’s Sherbrooke was the home of rival gangs the Gitans (formerly the Dirty Reich), and the Atomes. They were basically hooligans who rode motorcycles, did a lot of drugs and dabbled in a few organized crime activities. And when they crossed paths, things often got ugly, leading up to the so-called Night of the Long Knives in March 1974, in which the two gangs got into a rumble, which spilled over into various parts of the city, including in the emergency room of the St. Vincent de Paul hospital. By the end of the night two Atomes were dead, and several bikers were injured. Policing being what it was, no one went to jail for any of it.

In the years afterwards the violence became more sporadic, and it seemed the gangs were fading. Slowly the Gitans picked off or patched over the remaining Atomes.

Provincially, there was a Montreal gang called the Popeyes, who were itching to get into the big leagues, so in 1977 they tossed out their gang colours and became the very first Hells Angels chapter in Canada. They then went to war with the Outlaws in what became known as Quebec’s First Biker War, and by 1984 they had chased the Outlaws out of Quebec. Not long afterwards the Gitans, now the only motorcycle club in Sherbrooke, became Hells Angels as well.

By this point the Hells were getting serious about business, building up their network of drug dealers and establishing ties with the big boys of organized crime, like Montreal’s West End Gang and the mafia’s Rizutto family. Their credo was simple: less partying and general hooliganism and more business.

But the Laval chapter, also known as the North Chapter, apparently didn’t get the memo. They still liked having fun and causing trouble. But when they started using drugs that they were supposed to sell, and then started skimming the profits, the Montreal chapter saw a problem. Something needed to be done. How about a party in Lennoxville?

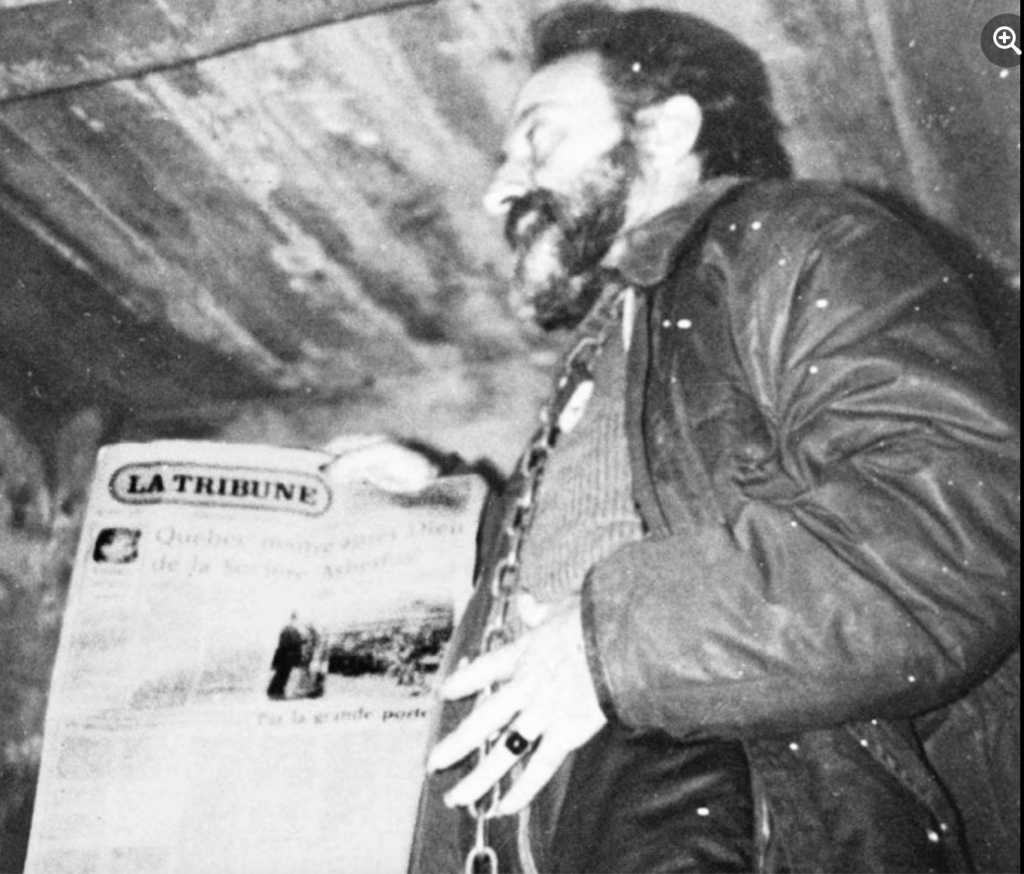

When eight members of the Laval chapter showed up at the Sherbrooke clubhouse (located just on the Lennoxville side of the line on Queen St.), they were welcomed inside. Then, with members of the Montreal, Sherbrooke and Halifax chapters present, five of them were gunned down. The remaining three Laval bikers were then made to clean up the mess and dispose of the bodies.

Years later, when I was working as a newspaper reporter, I got to see the inside of the bunker following a raid by the Sherbrooke Police. It was a rather unsettling feeling standing in the room where the massacre took place.

After the shooting, the five bodies were then put in sleeping bags and weighed down with cinder blocks and dumped into the St. Lawrence River near Sorel. Two of the Laval cleanup crew were forced into retirement, and the third was reassigned to the South, or Montreal chapter. Two weeks later another man, Claude (Coco) Roy, was shot by fellow gang member Michel (Jinx) Genest.

That was that. Until a fisherman in Sorel snagged a body in three months later. Sûreté du Québec divers found the rest, and the Lennoxville Massacre came to the public’s attention.

“At that moment (in 1985), the Hells Angels were doing a real cleanup to become a real criminal organization,” said André Cédilot, a reporter with the La Presse newspaper who covered organized crime at the time.

Eventually, out of the 41 people present at the Lennoxville Purge, five men were given life sentences for the murders. They were all were released on parole between 2004 and 2013.

But all was not well in the biker world. Most notably brothers Salvatore and Giovanni Cazetta decided to form the Rock Machine in 1986, rather than join the Hells Angels. Initially the two gangs opted to coexist. Until one of the Cazetta brothers got nabbed in the US while trying to smuggle 200 kilos of cocaine and went to prison. The Hells decided the time had come to take over all street-level cocaine sales in Quebec.

The resulting bloodbath between the Hells Angels and the Rock Machine would last more than 15 years. Through the many twists and turns, the final body count was 162 dead, including several innocent bystanders. There were 84 bombings and over 130 cases of arson. Though the Rock Machine joined forces with the Bandidos, most of them ended up dead or arrested. The Bandidos imploded in 2006 following an internal massacre of their own in Shedden, Ontario.

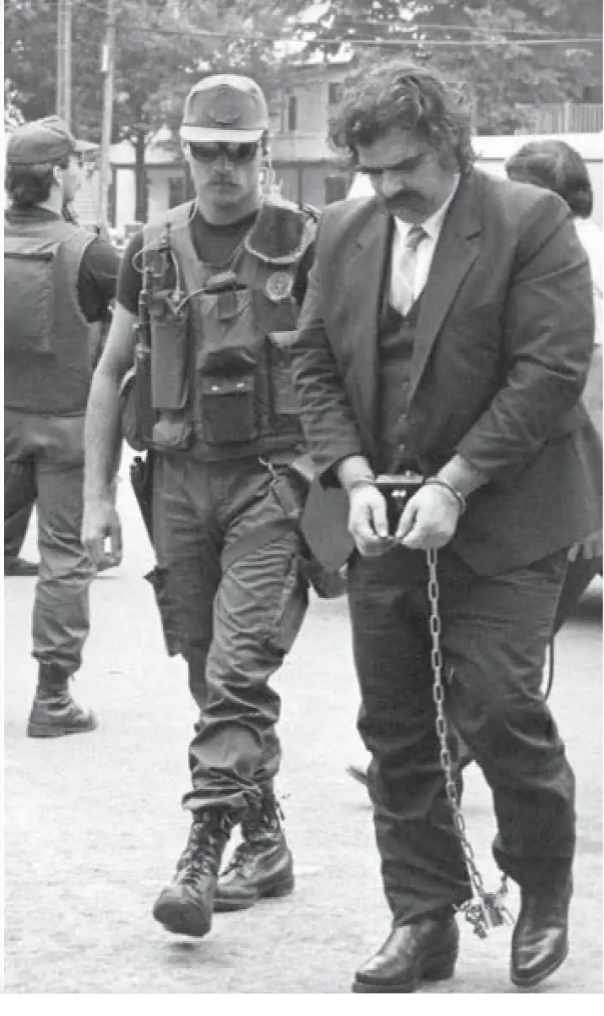

The Hells Angels were targeted by police many times during the biker war, with raids, arrests, jail sentences, releases, bikers informing on bikers, you name it. In a 2009 operation 156 Angels were arrested in Quebec, New Brunswick and France. But in 2015 the charges against most of them were dropped, the judge deciding that things had dragged on too long.

From the mid 1990’s to the early 200’s, I got to cover a few biker-related cases. Like the raid I mentioned earlier, where I also got to see one of Sherbrooke’s SWAT team members easing his way towards the house, rifle at the ready, when one of the Hells guard dogs came up and licked his face.

And there was the humour of seeing the Evil Ones, a Hells Angels puppet gang, being dragged into court. Being primarily francophones, they called themselves the “Heevils Ones.” I got a kick out of seeing a group of guys who belonged to a gang that they couldn’t even pronounce the name of properly.

There were literally dozens of twists and turns in the biker war saga, of bikers turning informant, settling of accounts, and so on. Two provincial prison guards, Diane Lavigne and Pierre Rondeau, were murdered on orders from Hells Angels Nomad leader Maurice (Mom) Boucher. There were even plans to kill police officers, Crown Prosecutors and judges, but those fortunately didn’t pan out. Boucher was convicted 2002 of ordering the prison guard murders, and sentenced to life behind bars. He died of throat cancer in 2022.

The dust may have settled, but the Hells Angels are still out there. The clubhouse was torn down in 2021, and the organization is a little quieter these days, but they’re still out there, doing their thing. Taking care of business.