Charles Marion spent 82 days chained up in a hole in the ground in Gould

I have long had an interest in the way violence impacts everyone. Not just the victim, but their family, friends, even their community. And the violence of what became known as the Marion Affair, the longest kidnapping in Canadian history, is no exception.

“For many people, the Marion Affair was a simple news item,” Pierre Marion, son of the kidnap victim, told Radio Canada recently. “But for those of us who lived through it, it upended our lives.”

In 1977 Charles Marion was a loan manager at the Caisse Populaire de Sherbrooke Est on King Street East. A longtime employee of the credit union, the 57-year-old lived a fairly typical, quiet life with his wife and kids. And sometimes for a break he would go to his cottage in Stoke, which he named “Mon Repos.”

On August 6, 1977, he was taking it easy at Mon Repos when several masked men broke in and grabbed him. They tied up his companion, a female coworker from the Caisse Pop, and locked her in a shed. Then they bundled Charles Marion into his van and left the scene.

At first no one knew anything was wrong. But Marion’s wife became suspicious when she couldn’t reach him, so she headed out to Stoke. She found his companion, who by this point had been tied up for 18 hours. The awkward conversation would have to wait. The police were called, and the manhunt began.

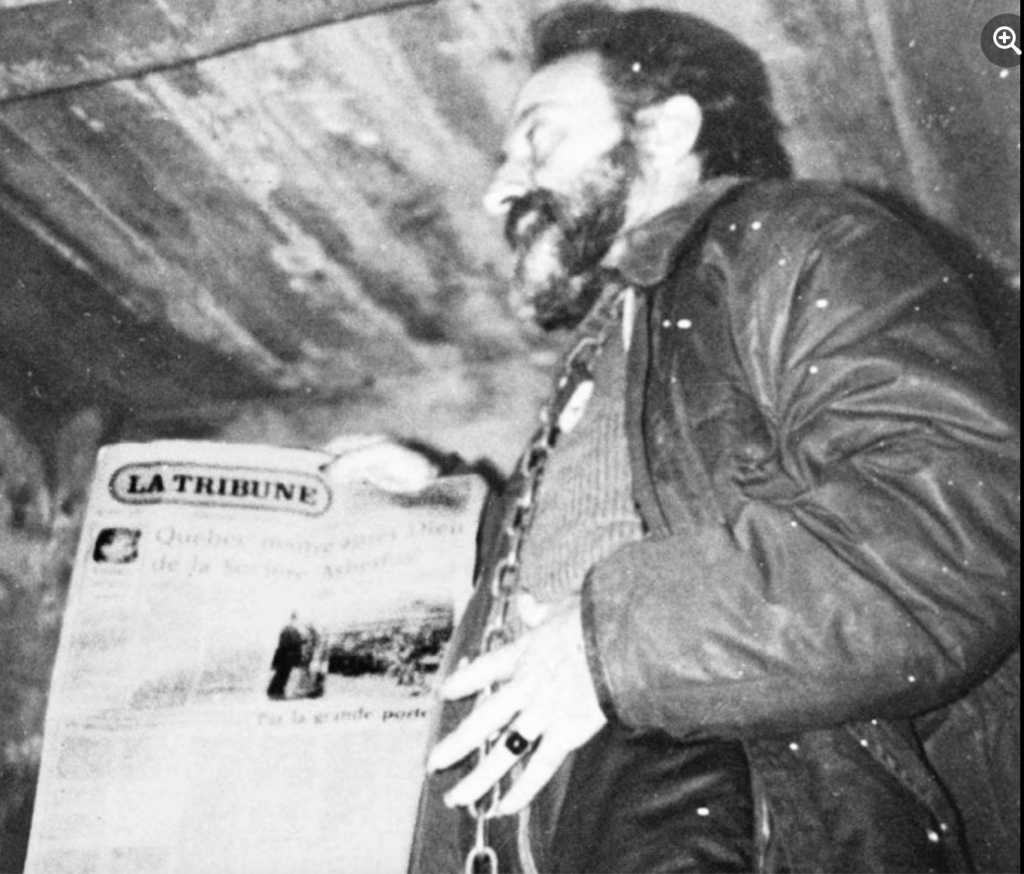

As for Charles Marion, he was blindfolded and taken to Gould. There his kidnappers had dug a hole in the ground, poured a thin pad of concrete, built some rough wooden walls and a ceiling, and then covered it all with dirt and branches. This would be his home for the next 82 days.

To say the man suffered is an understatement. He was chained to a steel rod set in the concrete, with the chains holding him by his arms, legs and neck. The kidnappers rarely fed him, other than gin and tranquilizers to keep him quiet. Most of the time he sat in the dark, fetid hole, with no idea of what lay ahead. Twice he tried to take his own life rather than continue his living hell.

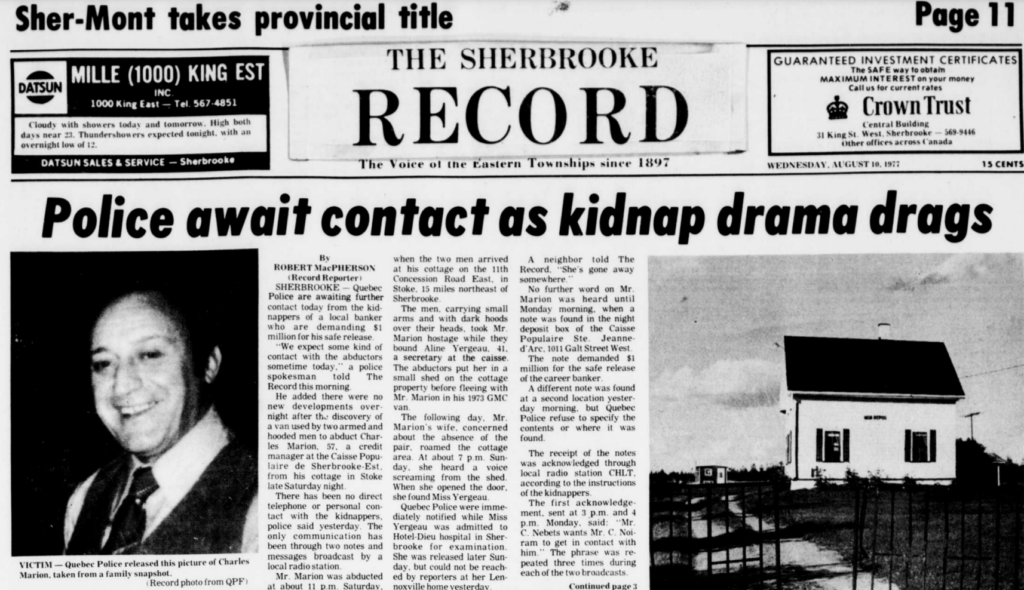

Meanwhile the family received a ransom note from a group calling themselves “Les Sept Serpents,” demanding a $1 million ransom (the equivalent of about $5 million today). The local media, including Sherbrooke Record reporters Janet Cotton, Robert MacPherson and photographer Perry Beaton, covered the mayhem.

After the initial search involving some 200 Sûreté du Québec officers turned up nothing, the SQ changed tactics. They agreed to pay the ransom but tried to pass off pieced of cardboard for the cash. When two men tried to pick up the ransom at Belvidere Heights in Lennoxville, they were ambushed by game wardens out looking for poachers. Then the police started shooting. In the resulting confusion and gunfire, the men managed to escape. Meanwhile the game wardens went home to change their underwear.

With the Caisse Populaire refusing to pay the $1 million ransom, the family continued to plead with the kidnappers, often through the media. They even got radio station CHLT to broadcast coded messages as a part of the negotiations. Photos of Marion, holding a current issue of the La Tribune newspaper, were released as proof of life.

In the end the family managed to raise $50,000. Far short of the original objective, the kidnappers finally agreed to accept it. On October 26, Pierre Marion, Charles’ son, accompanied by a police officer took the cash to Sand Hill in Cookshire. There, guided by CB radio, they dropped it off. The following evening Charles Marion, emaciated, bearded but alive, was found near the Sherbrooke Airport in East Angus. He had been delivered there on the back of a motorcycle wearing blacked out goggles.

If this was a movie, everything would wind up very neatly from this point. But real life is messy and doesn’t adhere to convenient timelines. In fact, it was eight months before Michel de Varennes, Claude Valence and his wife Jeanne were arrested. The ransom money had been marked with invisible ink, and the men were, naturally, trying to spend it.

Traumatized by the experience, Charles Marion tried to move on. But in the process the SQ had raised the possibility that Marion had been in on the kidnapping all along. Rumours can spread like wildfire, and soon the Marion family felt they could no longer trust their friends and neighbours.

In the end, Varennes was sentenced to 12 years in prison, and Claude Valence to 6 years. Charges against Jeanne Valence were seemingly dropped, and the other people Marion said took part were never caught. Though the trial revealed Charles Marion was truly the victim, the SQ have never apologized. In 2022 Pierre Marion released a book, 82 jours: l’affaire Charles Marion.

“He wanted to turn the page, but deep down he never managed to turn it,” Pierre Marion said. “He lived with public opinion, which always thought that he was partly responsible for this.”

Charles Marion was never able to return to his old job, and struggled to pick up the pieces. Traumatized by his treatment during and after the kidnapping, alienated from his community, 22 years later he took his own life in 1999 at the cottage where it all began.

And a family continues to try to make sense of it all.