The hanging of William Gray was big news in Scotstown – though passed almost unnoticed everywhere else.

It always surprises me how much attitudes on various issues have changed over the years. Like how blasé the wider world was when Scotstown’s William Gray was hanged for murder in 1880.

“Hanged today – William Gray, the murderer of Thomas Mulligan at Scotstown, was hanged at Sherbrooke this morning. He was cool and collected to the last, and died protesting his innocence,” wrote the Quebec Daily Mercury on December 10, 1880.

That’s it. On page three, next to items about how electric lights were being tried out in New York City for the Christmas season, and the completion of the railway link between Sherbrooke and Lévis. Two pages after an ad for Chamberlain’s Eye Ointment.

But you can be sure it was a hot topic of conversation for the people of Scotstown. Life in the tiny, remote, predominantly Scottish settlement was tough, and everyone knew everyone. So, when Mulligan’s remains were found, people took notice.

Maintained his innocence

Here’s what we know from the court’s point of view: Gray, a labourer, went to Mulligan’s house for a drink on December 20, 1879. They probably spoke Gaelic, like many of the 20,000 Scots who lived in that end of the Eastern Townships at the time. Forced off their homeland during the Highland Clearances of the 1830’s and 1840’s, they clung to their language, culture, and each other as they tried to carve out new lives in a harsh environment. While most of those early settlers later moved away, Gaelic could often be heard in that part of the world well into the 20th century.

At some point during the booze-fueled visit things turned ugly, and Gray used an axe to murder Mulligan. Upon sobering up Gray feared he would face a murder charge, so he returned to Mulligan’s house the next day and set it on fire.

It was only on Christmas Day that neighbour Alexander Scott noticed he hadn’t seen Mulligan around, and decided to go check on him. What he found was the burned out remains of the cabin, and a horribly burned human body, apparently Mulligan’s.

Before long the authorities came to suspect Gray. They arrested him and during questioning he let it slip that he knew of Mulligan’s death even before Scott discovered the body. A search of Gray’s house revealed some furniture and personal effects belonging to the victim, total value $34. He couldn’t really explain himself.

The authorities (calling them police might be a bit of a stretch) also received a statement from another nearby resident, a Mr. F. H. White, who claimed that Gray confessed the murder to him.

Throughout all this Gray protested his innocence. His lawyer, Robert Short, alleged there was no legal proof the body was that of the victim, and that the calcified corpse gave no evidence as to cause of death. Crime scene investigation and forensics being what they were in Victorian rural Canada, the circumstantial evidence pointed to murder. A jury returned a guilty verdict on October 6, 1880, and Judge Marcus Doherty handed down the death penalty. Gray was sent to the Winter Street jail in Sherbrooke to await his fate.

He didn’t have long to wait. On December 10, 1880, less than a year after the murder, Gray was led up the stairs of the portable gallows set up at the Winter Street jail for the occasion, and John Robert Radclive, Canada’s first official executioner, carried out the deed. Gray struggled for six minutes, hanging for ten minutes in all, before being declared dead.

Unhappy hangman

While the hanging of a murderer was no more than a curiosity for the average newspaper reader, for Radclive it was serious business. He was known for being a conscientious and kind man in dealing with his subject matter, but there were a few botched jobs in there. Like when he would miscalculate how far the prisoner would have to fall for a quick death, resulting in prolonged choking (up to half an hour) or, in at least one case, ripping a woman’s head off.

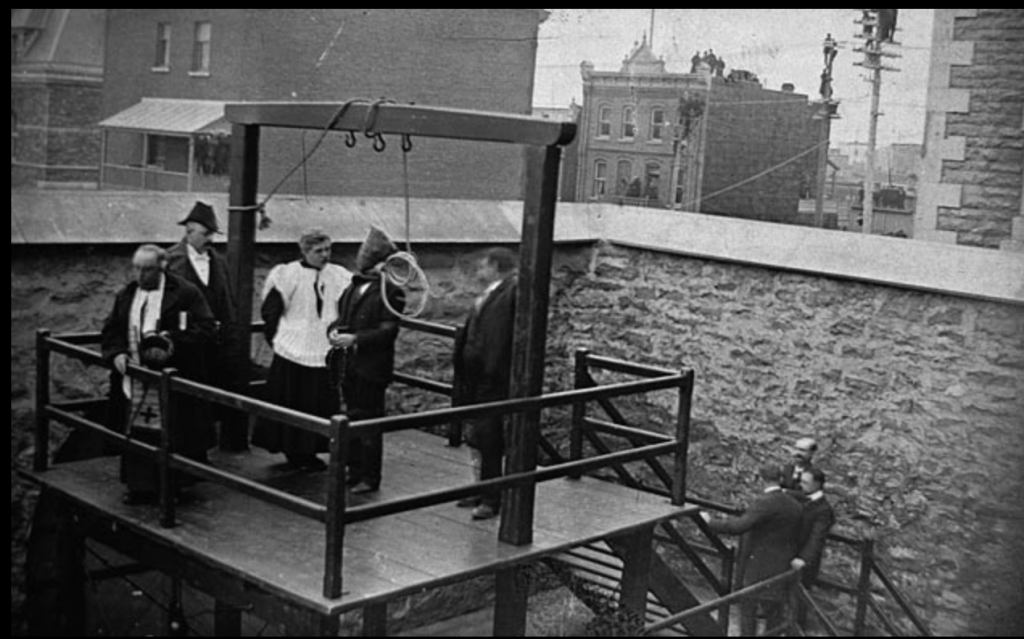

Photo: The hanging of Stanislas Lacroix, March 21, 1902 in Hull, Quebec. Note people watching from utility poles. People can be a bit sick sometimes. (Image taken from Wikipedia)

It would be easy to write off Radclive as a state sanctioned murderer. But the fact is he suffered greatly for his chosen profession. He claimed to have overseen more than 200 hangings, and expressed deep remorse for his involvement in so many deaths later in life.

“I had always thought capital punishment was right, but not now. I believe the Almighty will visit the Christian nations with dire calamity if they don’t stop taking the lives of their fellows, no matter how heinous the crime,” he said. “Murderers should be allowed to live as long as possible and work out their salvation on behalf of the State.”

A traumatized Radclive died in Toronto at the age of 55 from alcoholism.

Shifting attitudes

By the time of Gray’s hanging, Canadian opinion on capital punishment had already begun to shift. In 1840 the execution of an innocent man in Windsor, Ontario, resulted in the abolition of the death penalty across the river in Michigan. On the Canadian side the laws were revisited after Confederation, with the offences punishable by death reduced to murder, rape and treason.

The idea of public executions in Canada dropped away as well, with the last public hanging taking place in Goderich, Ontario in 1869. Once again, the evidence could have, by today’s standards, pointed to any one of several people rather than the man who ended up feeling the bite of the noose.

I have never understood the idea of wanting to witness an execution. Yet the appetite remained, and in an archival photo of the execution of Stanislas Lacroix in Hull in March 1902, people can be seen clinging to utility poles, trying to get a view of the event. Human nature is strange sometimes.

The hangings continued, and between 1867 and 1976, some 710 people were executed by hanging in Canada. The last two were carried out at Toronto’s Don Jail in 1962, with most murderers receiving life sentences instead. Shortly afterwards a moratorium was placed on the death penalty, and it would take another 13 years to finally make it a thing of the past.

Today almost no one remembers William Gray, or any of the half dozen other people who were executed at the Winter Street jail over the next century. It was closed in 1990, but remains as an empty, hollow stone monument to the history of crime and punishment in the Eastern Townships.

Hi, Thank you for writing this. I never knew this story. It’s amazing how much information you were able to collect about him, and about those times.

I was just shocked at how something as major as a hanging could be such a minor news item. We have evolved, thankfully.