Ever dally in Dunboro? Make it to Manville? Been to Boynton? Lived it up in Lawrence Colony?

One of the things that I love most about the Eastern Townships is how, after living here my entire life, working at jobs that take me all over the region (journalist, truck driver, daytime nomad), I’m still discovering new places. You might think you know the Townships, and you may indeed know a lot of places. But I can pretty much guarantee there are still some undiscovered nooks you’ve yet to see. Like Flodden, or Glen Farnham, or Lineboro to name but three. How about Ticehurst Corners?

For the early settlers, the region didn’t come with operating instructions, so they pretty much had to make it up as they went along. Moving into country that was for the most part uninhabited and unmapped, these settlers had to make the best of the situation. The discovery of a river might be a barrier, or it might be a good place to establish a mill. Mills attract business, which attracts people, and before long you have houses, and more businesses. Or not. History can be a little finicky that way.

Many of these forgotten locales were named after the local grist or sawmill owner. Call’s Mills, Ladd’s Mills, Hunter’s Mills, Savage Mills. Or the first person to open a post office, a genuine lifeline to the outside world. Places such as Farnboro, Farnam’s Corners or Bolton Forest. Occasionally, the name came from somewhere else entirely.

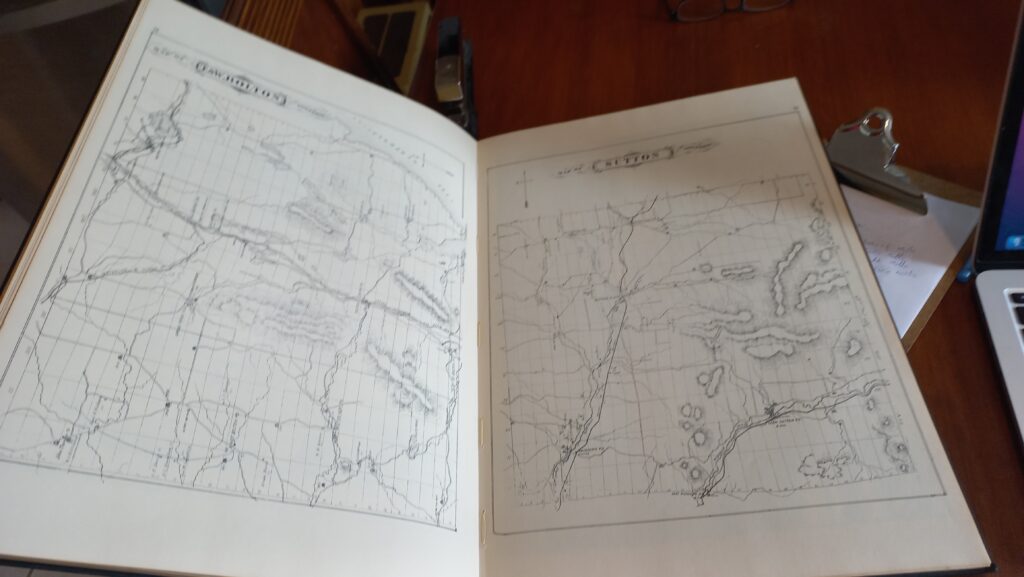

The 1881 H. Belden Historical Atlas of Quebec Eastern Townships doesn’t cover much east of Sherbrooke but remains a treasure trove of Townships place names and personalities. It was reprinted in the early 1970’s, so you can still find copies floating around here and there.

Take for example the village of Lost Nation in West Bolton. In its day it was a thriving little settlement, complete with a tavern, schoolhouse, general store, and other conveniences of the era. It was even a stop on the Stanstead to Montreal stagecoach line. All based on a thriving lumbering industry that attracted farmers from miles around to make some extra money in the winter, living in bunkhouses while their wives and kids tended the homestead in the quiet, cold months.

The one thing lacking in what those hardworking folks had to that point called Pleasant Valley was a church. Then one day in about 1838 some travelling “preachers” showed up, taking over the schoolhouse for a good old Christian revival. After much preaching and screeching the pastors passed the collection plate. This was followed by more pulpit pontifications, and another round of the collection plate.

By this point the locals, for whom money tended to be in short supply, got suspicious. Things started to get ugly and before long the preachers were being chased out of town, allegedly shouting over their shoulders “Oh what a lost nation of souls is this!”

The name stuck. So did the curse. A few years later a new, faster road bypassed the village, and the railroad line passed through nearby Knowlton, ignoring Lost Nation. The presence or absence of a rail line was, for these tiny settlements, the difference between prosperity or poverty. Today there’s really no sign that Lost Nation ever existed.

A similar fate for Griffin’s Corners in Stanstead Township. It was the first stagecoach stop after the Stanstead Plain border crossing on the way to Copp’s Ferry (now known as Georgeville), for people going to Montreal. In those early years Griffin settlers established a tannery, a blacksmith, a potash works and inns to house travellers. Being on the stagecoach line meant a post office as well. The Methodists, Universalists and Baptists shared one of the region’s first churches, built in 1841.

But with the advent of rail travel, and the lack of a nearby rail line, the settlement began to fade, houses falling into disrepair, businesses closing down. When the church burned in 1933, there wasn’t enough of a congregation to rebuild it. By then, to quote local historian Matthew Farfan, the only thing growing was the cemetery.

In some of these places even the cemetery is barely more than a memory. Back to Flodden, for example. It’s located on a dead-end road of the same name off Route 243 between Richmond and Racine, along what is known as Melbourne Ridge. And yet a person I know who had been there as a kid had to ask directions to find the overgrown graveyard. There’s no ghost town, because even the ghosts have left.

Today, with larger towns and what we might even call small cities well established, these places are fading from the collective memory. Houses fall into disrepair or are replaced. You don’t need a cheese factory at Fordyce Corner anymore because you can get your cheese when you get the rest of your groceries at the IGA in Cowansville, a ten-minute drive away. Same goes for church if you’re so inclined.

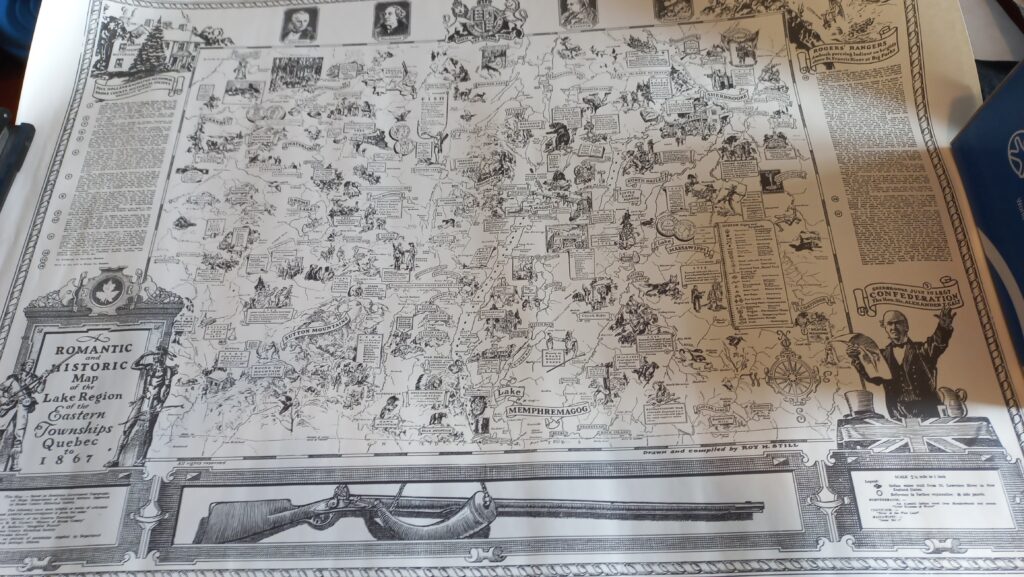

I have always loved maps, and the Romantic and Historic Map of the Lake Region of the Eastern Townships is folklore in print, filled with place names, local legends, and historic events.

The names occasionally show up on a map here and there. Or survive as a road name. Or be bandied about when you chat with an old-time Townshipper who likes to tell stories. “So, he come up there past Corry’s Corners, truck all loaded up with…” These are the same storytellers who will reference a location by the name of a farmer who lived there two or three generations ago. I love those stories.

Yet, despite their disappearance, I’d like to think that these place names helped shape who we are and how we view this region we call home. They contributed not just to the early settlement of the region, but to the overall flavour. Something uniquely Townships. Uniquely us.

With a little luck I may squeeze another three or four decades out of this life. And I plan to spend as much of it as I can discovering these little nooks, these out of the way places. Should I be blessed with such longevity, I can almost guarantee I still won’t have seen it all.

And that’s okay with me.